Stable Body Positioning

It’s time to jazz things up a little. Time to implement whole-body rotation and translation!

In earlier posts, I explained how I derived inverse kinematics equations for a quadruped and implemented them in code. To clarify, inverse kinematics is a method of calculating joint angles to allow an end-effector to achieve a desired position; this is seperate from stable body positioning, which describes how the quadruped’s body can be moved while keeping all its feet in the ground. In general, these movements can be categorized into two types: translation and rotation. Translation consists of moving forward-backward, side-side, and up-down while maintaining the body’s orientation with respect to the ground, while rotation describes pitch, roll, and yaw for the upper body. In this post, I’m going to describe how I derived the formulas for these movements and combined them with my inverse kinematics engine to work consistently.

Let’s start with the rotation stuff, specifically, pitch. Here’s what that looks like:

The first thing to point out is that rotations must keep the cneter of mass stable; they pivot around the center of mass, and don’t just rotate. This means that increasing the height of the front legs while decreasing those of the back by the same amount won’t work, since this will cause the center of mass to move backwards. To counteract the motion backwards, it is necessary to lean forwards, which means pushing the feet forwards. But by how much? - Food for thought…

Here are the diagrams I’ll refer to:

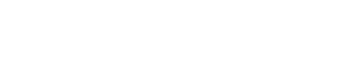

Diagram 1:

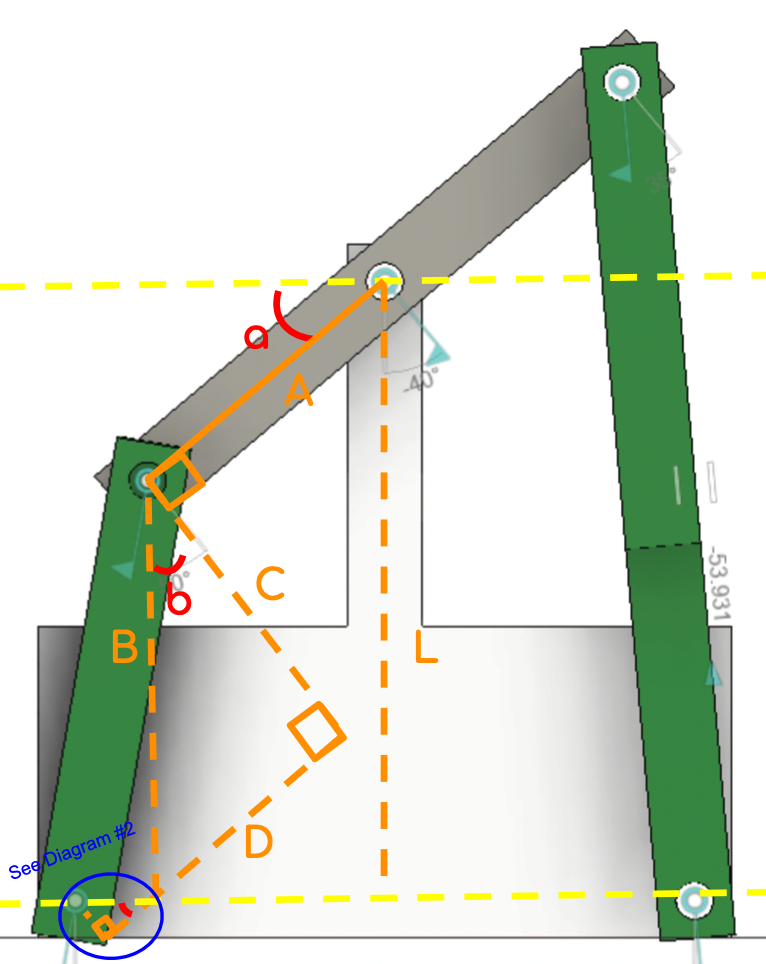

Diagram 2:

Where:

- a is the angle of pitch

- b is an arbitrary angle equal to a

- e is an arbitrary angle equal to a

and

- A is half the length of the robot’s upper body

- B is the distance from the shoulder directly to the ground

- C is the foot’s distance on the z-axis relative to the robot

- D is the foot’s distance on the x-axis relative to the robot

- E is an arbitrary distance below the foot along the x-axis relative to the robot

- F is an arbitrary distance below the foot along the z-axis relative to the robot

- G is the distance between the foot and the shoulder along an axis parallel to the ground

- L is the robot’s height from the ground.

To start, it is necessary to point out that all foot coordinates must be determined relative to the robot. Since the robot should be tilted, it is no longer parallel to the ground foot positions relative to the ground must be considered more seriously (I’ll get to this later), so it is necessary to transform the robot coordinates to the ground coordinates, or vice versa. My solution to this problem is to perform all calculations relative to the robot while considering only the foot position relative to the ground as the setpoint (which may sound obvious, but took me a while to figure out). In order to make this more clear, I decided to break up the foot’s position into it’s relative x-y-z components — since this is pitch, only x-z componenets — which are represented by lengths C and D. These are the side lengths that can be fed to the inverse kinematics engine.

Firstly, angles a and b are equal (this can be proven easily by considering the 90° angle between sides A and C) and triangle B-C-D is right. It follows that:

\(C = B\cos(a)\)

\(D = B\sin(a)\)

As the pitch angle increases, however, the shoulder actually moves towards the axis of rotation and futher away from the foot (the distance between the shoulder and the foot is referred to as length G). This must be considered as well — refer to the up-close diagram.

\(G = A(1 - \cos(a))\)

\(F = G\sin(e)\)

\(E = G\cos(e)\)

Where F and E are offsets from C and D, respectively. The foot should lie at point

((C - F), (D + E)) relative to the robot.

It’s as simple as that! This set of math should be applied to all four legs. Just don’t forget to make sure that the offsets are applied to each leg correctly, and that the sides that are moving down and those moving up are considered. For example, the rear legs in the diagram are modeled a little differently:

And so on.

This can also be used to find roll, since that movement is inherently the same, but for a different set of axis. Imagining the diagram to describe the rear of the robot, it becomes obvious that pitch is identical to roll.

Here’s the code I used for pitch:

for (int leg = 0; leg < LEG_COUNT; leg++) {

if (leg == 0 || leg == 1)

shoulderToGround = (float)(_originFootPosition.z + offsetZ) - (sin((float)pitchAngleL * ((float)PI / 180)) * ((float)BODY_LENGTH / 2));

else if (leg == 2 || leg == 3)

shoulderToGround = (float)(_originFootPosition.z + offsetZ) + (sin((float)pitchAngleL * ((float)PI / 180)) * ((float)BODY_LENGTH / 2));

outputFootPositions[leg].z += (cos(pitchAngleL * (PI / 180)) * shoulderToGround) - (_originFootPosition.z + offsetZ);

outputFootPositions[leg].x += (sin(pitchAngleL * (PI / 180)) * shoulderToGround);

twistZOffset = sin(pitchAngleL * (PI / 180)) * ((BODY_LENGTH / 2) - cos(pitchAngleL * (PI / 180)) * (BODY_LENGTH / 2));

twistXOffset = cos(pitchAngleL * (PI / 180)) * ((BODY_LENGTH / 2) - cos(pitchAngleL * (PI / 180)) * (BODY_LENGTH / 2));

if (shoulderToGround > (_originFootPosition.z + offsetZ)) {

outputFootPositions[leg].z += twistZOffset;

outputFootPositions[leg].x -= twistXOffset;

}

else if (shoulderToGround < (_originFootPosition.z + offsetZ)) {

outputFootPositions[leg].z -= twistZOffset;

outputFootPositions[leg].x += twistXOffset;

}

}The movement for pitch also makes sense intuitively, I think. In order to tilt downwards, the robot’s front height must decrease, and its rear legs must increase in height the same amount. Since this moves the center of the robot forwards, however, it is necessary to also shift backwards, which corresponds to a significant change in the x-axis coordinate of each foot. Finally, since tilting causes the shoulders of the robot to move further away from the feet, the feet must push outwards to keep the robot from falling flat.

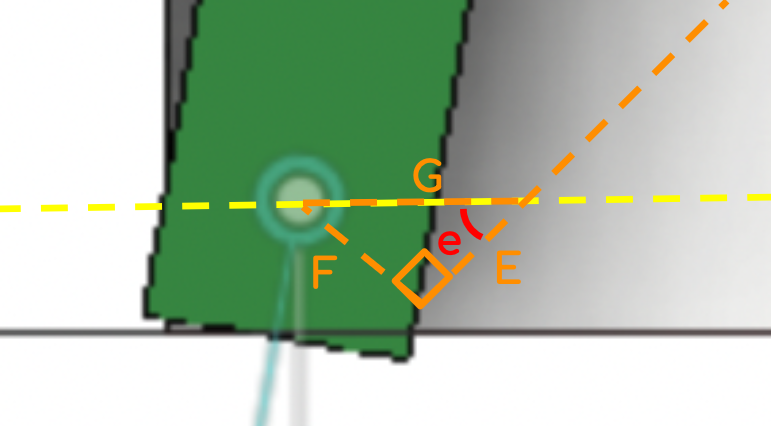

Now it’s time to move onto yaw. For that, I’m going to refer to this diagram:

Where:

- a is the angle of yaw

- b is an arbitrary angle equal to \(\tan^{-1}(\frac{C}{A})\)

- c is an arbitrary angle equal to b - a

and

- A is one-half the width of the robot

- B is the distance from the robot’s center to its shoulder

- C is one-half the length of the robot.

- D is an arbitrary distance from the center of the robot to its shoulder along the global y-axis (I have defined the x and y axis to be flipped)

- E is an arbitrary distance from the cneter of the robot to its shoulder along the global x-axis (I have defined the x and y axis to be flipped)\

- F is an offset relative to the robot’s shoulder along the global y-axis

- G is an offset relative to the robot’s shoulder along the global x-axis

First, let me point out that finding the offsets (lengths G and F) is the main goal of the calculation, since these are the lengths that can be fed to the inverse kinematics engine.

To understand how the calculations for yaw were derived, it is convenient to compare the robot’s un-yawed position (when angle a = 0) to it’s yawed position. Comparing the two positions makes it obvious that:

\(F = D - A\)

Thus, the difficulty is only in finding D and E. These can be found fairly straightforwardly when considering b, which is a constant:

And since b = c + a, it can be found that c = b - a. Calculating D and E is now a breeze:

\(E = B\sin(c)\)

\(D = B\cos(c)\)

Again, since

\(F = D - A\)

it is easy to find the distance the foot must be from the shoulder. Note that the height of the robot during the yaw doesn’t need to be account for, since this is

considered by the inverse kinematics engine.

Here’s the code for yaw:

for (int leg = 0; leg < LEG_COUNT; leg++) {

centerToCornerAngle = atan(((float)BODY_WIDTH / 2) / ((float)BODY_LENGTH / 2)) * (180 / PI);

centerToCornerLength = sqrt(pow((BODY_LENGTH / 2), 2) + pow((BODY_WIDTH / 2), 2));

footYOffset = centerToCornerLength * cos((90 - centerToCornerAngle - yawAngleL) * (PI / 180)) - (BODY_WIDTH / 2);

footXOffset = centerToCornerLength * sin((90 - centerToCornerAngle - yawAngleL) * (PI / 180)) - (BODY_LENGTH / 2);

if (leg == 0 || leg == 2) {

outputFootPositions[leg].y += footYOffset;

if (leg == 0) outputFootPositions[leg].x += footXOffset;

if (leg == 2) outputFootPositions[leg].x -= footXOffset;

}

if (leg == 1 || leg == 3) {

outputFootPositions[leg].y -= footYOffset;

if (leg == 1) outputFootPositions[leg].x -= footXOffset;

if (leg == 3) outputFootPositions[leg].x += footXOffset;

}

}So what about translation? Well… that was already solved by the pitch and roll calculations! The calculations used to account for the robot’s center moving further away from the shoulder can be used for translation as well — the translation amount is simply an input for G, and lengths F and E can be derived from there. If there isn’t a tilt, then G = E; conveniently, since e is the angle of tilt and cos(0) = 1, there is no need to change this calculation at all; simply assume that there is always an angle of tilt using the calculation from before, and translation will be account for.

Along the z-axis, things become even easier; simply use the robot’s reference height as the sum of its nominal height and z-axis translational offset.

Finally, it is important to point out that all the offsets solved for above should be accumulated before being sent to the inverse kinematics engine in order to be considered during a combination of movements.

Unfortunately, due to a hardware failure on my PCB (relay exploded… ‘underspecced’) I don’t have a comulative recording of yaw or translations working. Once I make my new pcb (in the works now!) I’ll add a video showing this stuff in action. It’s really cool!

Problems... so far:

- I haven’t found any! I ran extensive testing before my quadruped’s motherboard broke (again, relay failure) and it worked astoundingly well. In total the code is roughly 150 lines… definitely one of the larger functions in my code.

- In the future, I hope to solve this problem using linear algebra instead. Before solving this problem myself, I found multiple solutions (like this one, which applies it to posture correction) that used linear algebra to accomplish the same thing… and it is significantly less math. My senior year of high school, I’m going to take a linear algebra course in order to learn how this works.

I hope this helps! This solution took me nearly a week to figure out - the answer is much easier than I would’ve ever expected. Also, please note that I’m not releasing this on github yet; I’m in the middle of walking gait development, which I’d like to finish before making a new release. For that reason, github won’t be updated.

That’s all for now!